Daring River Raid Puts Bow on Union Conquest of Forts Henry and Donelson

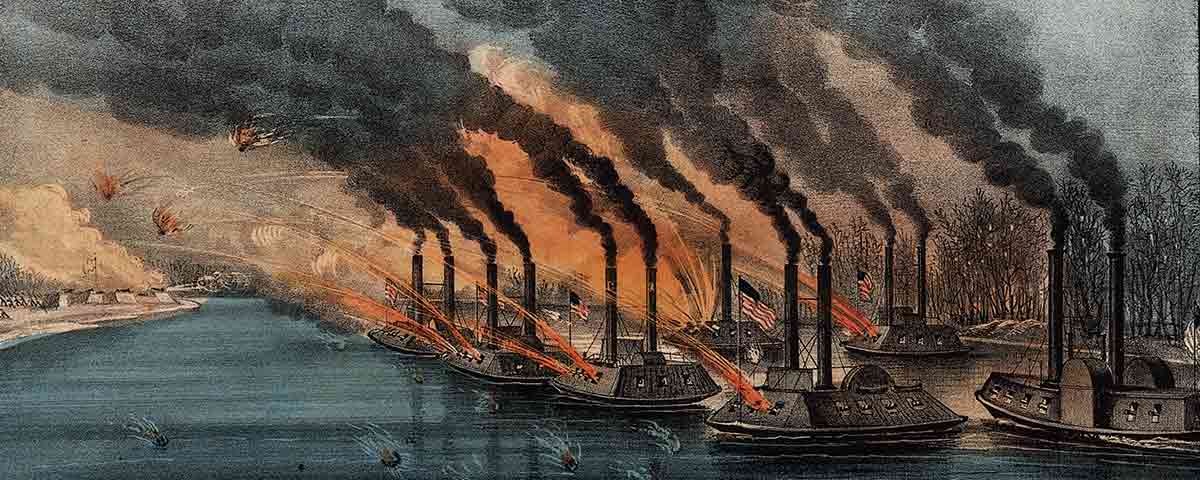

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]s he sent word of the capture of Confederate Fort Henry on February 6, 1862, Brig. Gen. Ulysses Grant kept his emotions in check, his victory telegraph an unassuming “Fort Henry is ours.” Union Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote, whose naval forces actually won the battle that day, reacted with a little more flair, writing his wife: “Bless the Lord who has given me the victory after a horrible fight of an hour and fifteen minutes.” Taking it even further was District of the Missouri commander Henry W. Halleck, who excitedly informed Washington: “The flag of the Union is re-established on the soil of Tennessee. It will never be removed.”

The biggest benefit of the victory, however, was not the capture of the fort itself, but that the Tennessee River was now open and vulnerable to thrusts by the Federal Navy. Without Fort Henry, the Confederates had no other fortifications blocking the river. If Union naval forces could now capture and destroy an important railroad bridge up the river, the Memphis & Ohio Railroad span a few miles to the south, it would puncture General Albert Sidney Johnston’s defenses and keep the Western Confederate forces from being able to communicate and move quickly. In effect, the wings of Johnston’s army would have to operate in the blind.

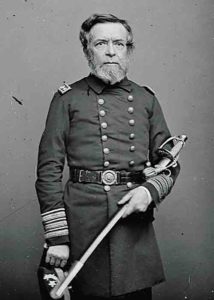

Already confident of victory at Fort Henry, Flag Officer Foote in early February had issued instructions to his most veteran naval commander, Lieutenant Seth Ledyard Phelps, to do the bulk of the dirty work on the river. A longtime Navy veteran, Phelps had three solid timberclads at his disposal: Tyler, Lexington, and Conestoga, which had been converted to gunboats and covered with wood, a sturdy alternative to the Union’s more famous City Class ironclads.

Phelps led his boats south immediately after the fighting at Fort Henry. He steamed hard, but because he had left fairly late he didn’t reach the Memphis & Ohio Railroad bridge until after dark on February 6. The span was actually a drawbridge, and Phelps found that the Confederates had closed it and disabled the machinery before they fled, meaning it could not now be opened. All the while, Phelps watched as “about 1½ miles above were several Rebel transport steamers escaping upstream.” He had gone as far as he was ordered, but he wanted so much more.

Thinking quickly, Phelps sent a party of machinists inland to get the bridge working. “In one hour,” he noted, “I had the satisfaction to see the draw open.” With nightfall and the need to secure the railroad, however, Phelps was torn between the bridge and his desire to hurry and catch the enemy boats, now with an hour’s head start. He left the slowest of his three gunboats, Tyler under Lieutenant William Gwin, at the bridge to take care of matters while he pursued with Lieutenant James Shirk and the faster Lexington and his own Conestoga. While Phelps sped away, Gwin and his crew spread out along the railroad and destroyed some of the trestle work leading to the bridge but not damaging the structure itself, thinking it would be useful when the Union armies pushed southward along the river.

All the while, Phelps raced on with Lexington and Conestoga. Over the next five dark hours, Phelps and Conestoga outran Lexington and managed to close the gap with the Confederate vessels, eventually forcing all three to halt. The first he caught up with, the Samuel Orr, “had on board a quantity of submarine batteries, which very soon exploded,” Phelps reported. The other two, the Appleton Belle and Lynn Boyd, huddled near the bank at the mouth of the Duck River and were destroyed by the Confederates themselves. One of them turned out to be laden with “powder, cannon shot, grape, balls, &c.” and provided quite a fireworks show deep in the night.

The massive explosion caused major damage to the surroundings, especially to a local residence on the bank of the river. Phelps reported it was “the house of a reported Union man,” and he suspected that “there was design in landing the Rebels in front of the doomed house,” which was, in Phelps’ words, “blown to pieces.”

So too would have been Phelps had he not realized what was happening and halted short of the two enemy steamers. Even at a distance of 1,000 yards, Phelps’ gunboat still sustained damage from the falling debris. “Even there our skylights were shattered by the concussion,” he noted, “the light upper deck was raised bodily, doors were forced open, and locks and fastenings everywhere broken.” He added, “the whole river for half a mile around about was completely ‘beaten up’ by the falling fragments and the shower of shot, grape, balls, &c.”

Enough was enough, Phelps decided. Having caught the enemy steamers and survived the encounter, he wisely stopped his advance to await daylight as well as Tyler and Lexington. The latter had no pilot on board, and was especially vulnerable in the dark. Fortunately, both timberclads arrived safely, and Phelps’ flotilla was intact again.

Phelps set out the next morning to inhibit more shipping on the river and to see how far he could go into Mississippi and Alabama. When the flotilla reached Hardin County, Tenn., at dark, Phelps found another prize. At the Cerro Gordo landing, he discovered the fabled Southern ironclad Eastport, still under construction. As the Confederate workers fled at Phelps’ advance, they peppered the Federals with rifle shots, though a couple of shells from the gunboats put a quick stop to that. “When we fired two 24 pounder shots at her the crew left it to us,” remembered one Tyler sailor.

Phelps wisely sent men to immediately check for “means of destruction that might have been devised,” and sure enough, the Confederate workers had scuttled the boat, allowing water in through broken suction pipes. Phelps’ naval personnel were able to stop the leaks, which provided the North with yet another ironclad. Phelps noted the Eastport was “in excellent condition, and already half finished.” Around the yard also lay large quantities of lumber and iron plating as well as sundry items intended for use on the gunboat. Phelps had made a major catch.

Eastport’s capture forced another decision on Phelps. He had always intended to travel along the river as far as he could go, but he certainly could not leave the ironclad alone, even with a small guard. If the timberclads left, it would likely be recaptured and sunk for good, Phelps reasoned. So he decided to split his force again, leaving the slower Tyler at Cerro Gordo with Eastport while he and Shirk moved on. Tyler’s crew was instructed to load all the valuable supplies and materials for the return north.

On February 8, Phelps and Shirk passed Eastport, Miss., and soon captured two Confederate steamers at Chickasaw. One, Sallie Wood, was laid up and not worth much, but the other, Muscle, was laden with iron intended for the Confederate government. Next for Phelps was Florence, Ala., “at the foot of the Muscle Shoals.” The lieutenant noted that the Rebel steamers Sam Kirkman, Julius, and Time had been driven ahead of him, with the Confederates eventually torching all three to keep them out of Federal hands.

Despite limited fire from the banks, Phelps quickly sent men ashore to save anything they could, and did manage to accumulate some supplies marked “Fort Henry.” Phelps had his men load all they could and destroyed the rest.

In the midst of the destruction, “a deputation of citizens of Florence” visited Phelps. The locals had gathered some old relics, including a cannon on a carriage missing its wheels, to defend their homes. They wisely thought better of it, opting to ask for mercy instead. Thinking the Federals were marauding vandals, they first asked “that they might be made able to quiet the fears of their wives and daughters with assurances from me that they should not be molested.” Phelps told them in no uncertain terms “that we were neither ruffians nor savages, and that we were there to protect them from violence and to enforce the law.”

Relieved, the citizens then discussed a more vital, economic concern: the railroad bridge crossing the river. Though important for Florence itself, the bridge was not on a main line, connecting instead with the trunk line of the Memphis & Charleston Railroad south of the river. Phelps again responded compassionately, stating that he could not proceed upriver even if the bridge was not there and “that it could possess, so far as I saw, no military importance.”

Phelps thus left the bridge intact. Not so with the Southern communication ability. The Confederate telegraph operator at Tuscumbia, south of the river, reported that the enemy took the Florence office and “found out nearly everything that was passing over the line before he was informed of their having landed.” The quick-thinking operator disconnected the Florence line “and cut them off.” One newspaper nevertheless claimed the invaders sent “some wondrous message to Richmond.”

Having gone as far as he could because of the shoals, Phelps turned around. It had been an extremely profitable raid. Phelps had captured three boats, including Eastport, and had forced the Confederates to destroy six more (though Southern reports indicated others were scuttled or burned out of the enemy’s view).

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Men, Women, and children several times gathered in crowds of hundreds, shouted their welcome, and hailed our national flag with enthusiasm.[/quote]

Despite his success, Phelps had left two major bridges in Alabama intact: the one at Florence, but more important the Memphis & Charleston span at Big Bear Creek near the state line. While losing the Florence bridge would have done little damage to the Confederate rail network, destruction of the Big Bear Creek bridge on a major Confederate trunk line that Leroy Pope Walker described as the “vertebrae of the Confederacy” would have been disastrous.

Phelps reached Cerro Gordo during the night on February 8, reuniting with Gwin and Tyler. That gunboat’s crew had been busy at work for the past 12 or so hours, loading lumber and preparing to set sail, and the crews of Lexington and Conestoga joined in after they arrived. According to Phelps, the raid had “brought away probably 250,000 feet of the best quality of ship and building timber, and the iron machinery, spikes, plating, nails, &c., belonging to the rebel gunboat.” Not wanting the local mill to provide any more lumber, Phelps also had it destroyed.

Though anxious to be on his way, Phelps learned of another possibility he couldn’t resist. Roughly 25 local residents had decided to join the Union Navy and told Gwin of a regimental encampment at Savannah just upriver. Phelps had passed the town twice that day, but had noticed nothing out of the ordinary. Now, he wanted the camp destroyed, and Gwin and Shirk agreed. This time, Phelps left Lexington to guard Eastport and took Conestoga and Tyler to Savannah. Gwin landed with several troops and a howitzer early in the morning February 9, broke up the camp, and then burned what they could not remove.

Phelps and his men were surprised by the extensive pro-Union sentiments in the region. “[W]e have met with the most gratifying proofs of loyalty everywhere across Tennessee,” Phelps wrote, “and in the portions of Mississippi and Alabama we visited most affecting instances greeted us almost hourly.” The lieutenant also reported, “men, women, and children several times gathered in crowds of hundreds, shouted their welcome, and hailed [our] national flag with an enthusiasm there was no mistaking. It was genuine and heartfelt.”

As the Federal vessels continued north later in the day, with Eastport, Sallie Wood, and Muscle in tow, the latter ship began to leak badly. Noted Phelps, “all efforts failing to prevent her sinking, we were forced to abandon her, and with her a considerable quantity of fine lumber.”

More trouble occurred when the flotilla reached the Memphis & Ohio Railroad span, when Phelps discovered the taller Eastport could not pass through the drawbridge for several hours. Phelps’ flotilla finally reached Fort Henry on February 10. Foote was obviously overjoyed at the news, writing Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles that Phelps’ work “has been thorough and merits the highest praise.” His subordinate, Foote would write, “has, with consummate skill, courage, and judgment, performed a highly beneficial service to the Government, which no doubt will be appreciated.”

There was no such celebration in the Confederacy. Reeling from the Fort Henry loss and fearing imminent action against nearby Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River, the South went wild condemning the naval events of early February 1862. In fact, one Confederate at Columbus, Ky., wrote his wife, “I hear the Yankee gunboats are at Florence, Alabama!” Newspapers reported that “the Lincoln gunboats seem to have had quite a frolic up the Tennessee.”

In the Confederate psyche, Fort Henry was the key that unlocked the Lower South, and newspapers in Memphis, Nashville, and New Orleans, among other locales, nervously reported the continuing increments of the Federal Navy’s thrust along the Tennessee.

These developments were not good signs, as subsequent events would bear out. Confederate officials scrambled to contain the damage. Both wings of the army’s Western defensive line retreated from Kentucky, and reinforcements were called up from New Orleans and Pensacola, Fla. In fact, the strategic concentration that led to the Battle of Shiloh two months later occurred as a result of Fort Henry’s fall and the psychological effect of Phelps’ raid deep into the Confederacy, rather than the more commonly touted events later at Fort Donelson.

Phelps’ raid blazed a trail that the Federal armies would ultimately follow. It refocused attention on the vulnerable Confederate west. At his Bowling Green, Ky., headquarters Albert Sidney Johnston faced some tough decisions—mainly courtesy of Seth Ledyard Phelps and his timberclads.

This article is adapted from Timothy B. Smith’s new book Grant Invades Tennessee: The 1862 Battles for Forts Henry and Donelson (University Press of Kansas, 2016).