Hoping to strike it big mining in the Philippines, brothers Walt and Jim Cushing instead made a name for themselves as guerrilla leaders fighting the Japanese

[dropcap]J[/dropcap]im Cushing was tearing up the town again. The 30-year-old Mexican American miner and his friend had drunkenly stumbled up to a cart driver in northern Mindanao in the Philippines and offered him a huge tip if he could deliver them to their rooms on the second floor of the Surigao City Hotel. Despite loud cries of encouragement from the two drunks in English, Spanish, and a local Filipino dialect, the horse and driver’s attempts to climb the steps failed. Fearing they would be held responsible if the animal broke a leg, the men called a halt to the spectacle. It was the dawn of 1940 and Jim’s intemperate lifestyle suited him just fine. As he later wrote, “I was not setting the world on fire.”

About the same time, 700 miles to the north, Jim’s older brother Walt, 33, was busy working the small gold mine he and two partners open-ed in Abra, a province in northern Luzon. Walt had gone through his own wild period after his wife left him 1937. Deep in despair, he blew all his savings on a nine-month bender, and in one dark moment signed up for the French Foreign Legion. Friends finally dissuaded his dissolution, got him back on his feet, and back into mining. Once again he felt settled and looked forward to a bright future.

The Japanese invasion of the Philippines the following year changed everything for the brothers. Always aggressive, Walt jumped right into the fray, while Jim took on a wait-and-see attitude. But destiny had something altogether different in store for each of them. Over the next four years, the guerrilla exploits of Walt and Jim Cushing would become the stuff of legend.

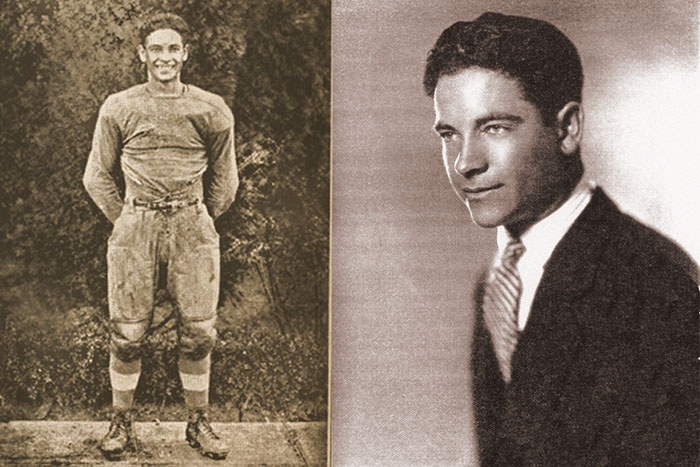

The boys were among the 10 children born in Mexico to silver miner George Cushing and his Spanish Mexican wife, Simona. They inherited the light brown complexion of their mother, the broad grin of their father, and grew up fluent in English and Spanish. In 1910 the Mexican Revolution tore apart the Cushing family’s prosperous life, forcing them to move to the safety of El Paso, Texas.

Walt was the runt, which may explain his drive to succeed. At only five foot six and 125 pounds, he was a star gymnast, football quarterback, soccer forward, and an Eagle Scout. Though offered a place at Notre Dame, Walt decided he wanted to see the world. He kicked around the U.S. for a few years, picking up odd jobs—barnstorming parachutist, skyscraper riveter, commercial diver. Then, in 1932, he sailed for the Philippines to try his luck at the family business—mining.

Jim was tall and husky, and reticent as a youth. He was always proud of being the “seventh son of a seventh son,” which he believed meant he would be lucky in life. But things started off slowly for him. He muddled along in school, was a middling athlete, and, after graduating, went to work making tires for the Goodyear company. In 1934, Jim tired of rubber and decided to seek his fortune in the Philippines, too. He soon found work as a mining mechanic for Mambulao Consolidated in southern Luzon, where he proved adept at handling explosives. In late 1940, he met a girl from Leyte, fell in love, and married her, settling down and seeming to take life more seriously.

The lives of both brothers got a lot more serious on December 8, 1941. While Jim first reacted to the Japanese attack by contemplating an escape to Australia, Walt was determined to defend his island home of the last 10 years. When he got word two days later that 2,000 Japanese troops had landed on Luzon at nearby Vigan, Walt eagerly headed to the coast to reconnoiter. There, he tried to persuade a local unit of the Philippine Army to help him repel the Japanese invaders. Instead, they denounced him as a “fifth columnist”—a foreigner working secretly with the enemy for his own gain—and sent him away.

Undeterred, Walt soon inspired 200 Filipinos to join him in fighting the Japanese. On January 18, 1942, he undertook his first big operation, leading his volunteers on an ambush against a 10-truck convoy. During the four-hour firefight that followed, Walt ran up and down the highway, a .45-caliber pistol in each hand, sticks of dynamite bulging from his pockets, shouting, “Give it to ’em boys!” When it was over, more than 60 enemy soldiers lay dead. He led more than 15 ambushes that spring, blowing bridges as he went.

But ultimately Walt’s efforts proved futile. The Japanese quickly overran northern Luzon, then turned their attention to Bataan and Corregidor. While the battles raged, President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered General Douglas MacArthur, commander in chief of the U.S. Army Forces in the Far East, to evacuate to Australia. “I shall return,” he famously vowed. On May 7, 1942, American forces in the Philippines surrendered unconditionally. The Japanese consigned tens of thousands of soldiers, and thousands of American civilians, to POW and internment camps.

In June, after sending his fighters home, Walt set out on a 300-mile journey from Abra down to Manila to raise money for his guerrillas. It was a fraught odyssey. One evening, he stopped at a sugar mill to seek assistance from the manager. While he was having tea, a dozen young Filipinas came to serenade their visitor. Just as the group broke into God Bless America, four Japanese officers appeared, forcing Walt to hide. When the girls finished, the enemy soldiers happily applauded their performance, unaware of the song’s significance.

On another evening, Walt stopped by a nightclub in Manila to fetch some intel from the owner. He was immediately recognized by a Japanese man who knew him from the mining business. Rather than run, Walt sauntered over to the table and shook hands with the man, who then asked why Walt hadn’t been locked up with all the other Americans. Walt said that he had been released for the day to visit the hospital and was returning to the lockup the next morning. As he left the club, he hoped he had not aroused suspicion, but when he returned to his hotel room, he found that it had been turned over, probably by the Japanese secret police—the dreaded Kempeitai.

These close calls did not divert the rebel leader from his fundraising mission; he persuaded several wealthy families to donate freely. He finally arrived back at his headquarters at the end of August 1942, exhausted but jubilant from his success.

Two weeks later, Walt set off with a three-man security detail to visit the camp of another American guerrilla commander. He had been warned that the people along his route were pro-Japanese, but felt his mission was too important to turn back. On September 19, Walt stopped at a farmhouse for dinner. After the meal, he stepped out on the veranda for a smoke. Suddenly, from the cover of the bush, a fusillade of shots rang out, instantly killing two of his bodyguards and mortally wounding him. As the enemy closed in, Walt killed six of them, then with his last bullet, turned his .45 on himself.

After nine months of fire and fury, Walt Cushing was dead. The Japanese were so impressed with his willingness to choose death over capture—which appealed to their samurai-inspired Bushido code—they gave him a proper funeral and burial at a churchyard.

It’s not clear when Jim learned of his brother’s death; they probably hadn’t seen each other for a year or more. But by the time Walt died on Luzon, Jim had become deeply entangled in his own guerrilla resistance movement on the nearby island of Cebu. The shooting war didn’t arrive there until April 10, 1942, when 12,000 Japanese troops stormed ashore at three separate beaches. As the enemy pushed toward Cebu City, besieged American commanders knew they had little time to destroy the island’s sprawling port. What they needed was an explosives expert, and Jim, with his mining background, fit the bill. The army commissioned him a temporary captain and turned him loose.

His first target was a quintet of oil storage tanks arrayed along the waterfront. He planted his dynamite, then waited until nightfall before pushing the plunger, knowing that the darkness would make the explosions more spectacular. “It turned night into day,” he recalled proudly. He then moved on to more mundane objectives—wharves, causeways, warehouses. In mid-May, when the Japanese began their final drive into the city, Jim and thousands of Cebuanos melted away into the jungles to continue the fight.

Something seemed to have snapped inside Jim after he obliterated Cebu’s port. He suddenly became a man obsessed with driving out the occupiers rampaging through towns and villages, brutally repressing any Cebuanos who dared resist. After the Japanese took Cebu, resistance movements began springing up across the island. Some had 50 men. Some had 200. Each was a distinct entity. But in order to be a truly effective guerrilla force, unity was a necessity. So local civic leaders in southern Cebu approached Jim about bringing order out of chaos by assuming the role of overall commander. They liked his manner, his fortitude, and hoped he could bring the disparate players together. After mulling it over, in late August 1942, Jim accepted the challenge.

While Jim gathered his men, another American, 35-year-old Harry Fenton—the prewar host of a popular local radio amateur hour who mixed music with virulent anti-Japanese harangues—was also building up a force in northern Cebu. In October 1942, Fenton invited Cushing to join him as co-commander of the Cebu Area Command (CAC). “I took over the combat and tactics,” Cushing wrote. “Harry took the job of organization.” They located their headquarters near the tiny barrio of Tabunan—an isolated, verdant valley barely 11 air miles from the center of Cebu City, and surrounded by steep, rocky mountains.

That November, Jim led his guerrillas on the first of a series of attacks on enemy outposts. During the raid on a garrison in the coastal city of Toledo, he was commanding the furious action when he abruptly arose to move in for a clearer view. Moments later, a mortar round made a direct hit on the foxhole he had just vacated, killing two men. It seemed the “luck of the seventh son” was with him that morning. Cebuanos, buoyed by the attacks, rained praise upon Jim Cushing.

The CAC’s co-command structure worked fine at first, but trouble was brewing. While Jim was generally well liked and respected by the people of Cebu, Fenton was secretive, suspicious, and feared by his own men. That fear stemmed from his paranoid campaign to rid the country of “spies” and “traitors.” His diary contains many entries like these: “3 spies executed yesterday,” “Two executions today,” “Lucy Miller executed today.” His behavior did not sit well with the guerrillas, who were sometimes the target of his conspiracies.

In mid-1943, with the enemy in pursuit, Jim disguised himself as a priest and went over to neighboring Negros Island to meet with Major Jesus Villamor, a Philippine Air Force officer sent in by General MacArthur to assess the resistance movement in the Visayas. When he arrived, the major, a national hero in his own right, did not know what to make of Jim. “From the shadows there emerged a man dressed curiously in the flowing black robes of a priest,” he later wrote. “He looked so frail. I almost felt a surge of disappointment. Was this the great Cushing?” Still, Villamor listened patiently to Jim’s pleas for official recognition from MacArthur in Brisbane, Australia, which would give the CAC direct contact with General Headquarters (GHQ), as well as access to much-needed supplies.

Returning to Cebu in November, Jim learned that his men had executed Fenton, whose increasing paranoia and erratic violent behavior had sparked a mutiny. Furious and shaken, sick in body and spirit, Jim retreated to his hut for several weeks. He came out of his depression in late December 1943, and firmly retook control of the CAC.

The long-sought recognition from MacArthur came on January 22, 1944. Jim Cushing was promoted to lieutenant colonel and appointed sole commander of the CAC, 8th Military District, U.S. Army Forces in the Far East. The following month, a U.S. Navy submarine delivered to Jim’s guerrilla unit its first load of supplies—guns, ammunition, medicine, and a long-range radio capable of reaching Brisbane. Jim felt his luck was holding steady.

On April 8, 1944, Jim got word that one of his volunteer units would soon arrive at his camp with 10 Japanese prisoners who had survived a seaplane crash just off the coast. He immediately transmitted the news to Brisbane, adding that “Constant enemy pressure makes this situation very precarious.” That was putting it mildly.

One of the captives turned out to be a rear admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy, Shigeru Fukudome, chief of staff to Combined Fleet’s commander in chief, Admiral Mineichi Koga. The two officers were en route from Palau to Mindanao on separate aircraft; Koga’s plane also went down when both planes ran into a tropical storm. Koga did not survive.

Jim had a real dilemma on his hands. He knew that GHQ was anxious to get the prisoners to Australia for interrogation. But the Japanese army knew that Jim’s men were holding Fukudome and began a frantic search. They swept through barrios, burning huts and killing men, women, and children in an effort to force Jim to release the admiral. On April 9, as troops neared Tabunan, Jim moved his headquarters and prisoners deeper into the jungle. Along the way, an enemy plane spotted and strafed his group, killing three rebels. In a running gun battle across Tupas Ridge, the remaining guerrillas made their escape. That night, Jim made a momentous decision to protect his people—his “Cebu patriots,” he called them—and hand over Fukudome.

He sent a message to the Japanese commander, Lieutenant Colonel Seiiti Ohnisi, saying he would release his prisoners only “on condition that your soldiers will stop the killing of innocent civilians.” In a return note, Ohnisi agreed—adding “the measure taken by you is a warrior like and admirable action. I expect to see you again in the battlefield someday.” Like his brother Walt, Jim had won the admiration of his adversary. The next morning, the admiral and his party were freed.

Although Jim Had given up valuable prisoners, his luck would reward him yet again. In the midst of the chaotic exchange, a native shopkeeper delivered to Jim a red leather portfolio that had been floating in the sea not far from Fukudome’s plane crash site. Inside were official-looking documents. Guessing they might be important, Jim informed GHQ that he still had “papers and field orders.” That caught their attention. On his own initiative Jim sealed the papers in empty mortar shells and sent them to the guerrilla commander on Negros.

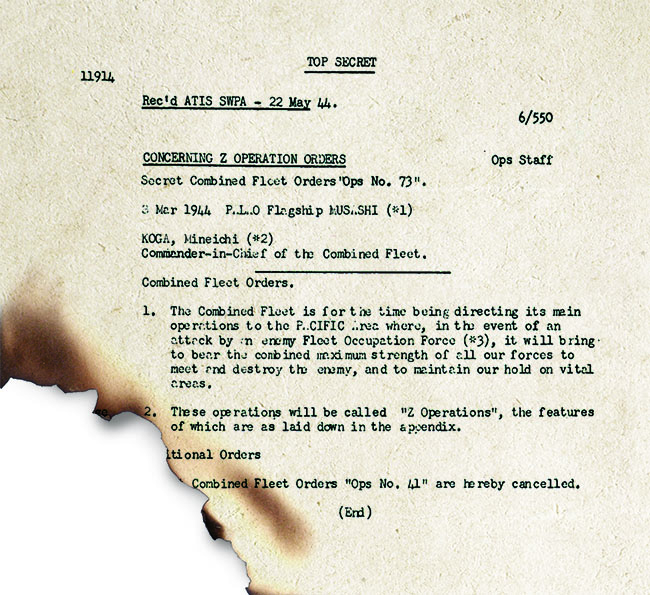

On May 11, 1944, the submarine USS Crevalle was diverted from its regular war patrol to pick up the cache. The vessel surfaced off the southwest coast of Negros and took aboard the mortar shells, as well as 41 Americans who had been stuck on the island since the start of the war. On May 21, the documents reached Allied translators in Brisbane. What emerged was Admiral Koga’s secret Combined Fleet orders—“Ops No. 73.” Called the “Z Plan,” it revealed a detailed blueprint for the Japanese defense of the Mariana Islands, by bringing “to bear the combined maximum strength of all our forces to meet and destroy the enemy.” That meant all land- and sea-based aircraft would be deployed to seek out and crush the American fleet. The force available to the Japanese was formidable: 1,100 planes and 88 warships.

Using this insight into Japanese strategy, Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, commander of the Fifth Fleet, successfully derailed their plan during the Allied invasion of Saipan, on June 15, and the epic Battle of the Philippine Sea, four days later. The enemy lost three carriers, two oilers, and, in what came to be known as the “Great Marianas Turkey Shoot,” nearly 700 aircraft along with their well-trained pilots, effectively ending Japan’s ability to wage offensive air operations. Writing about the effect the Z Plan had on the outcome of the war, National Archives archivist Greg Bradsher said, “the exploitation of the Z Plan was one of the greatest single intelligence feats of the war in the Southwest Pacific Area.”

On October 20, 1944, General MacArthur fulfilled his promise to return to the Philippines when he stepped ashore on Leyte. His arrival boosted the spirits of Cebuanos hoping for a quick end to their suffering. While they waited, Jim continued his fight, inflicting heavy casualties on the enemy. In March 1945, 23rd “Americal” Infantry Division troops finally liberated the island.

In the course of the war, CAC’s 8,700 guerrillas chalked up quite a record. In 218 organized encounters, they killed more than 10,000 Japanese and tied down thousands more in occupation duties. In 1945, the army awarded Jim Cushing the Distinguished Service Cross, the United States’ second-highest valor medal. His citation noted that his “courage and resourcefulness enabled him to inspire in the people of Cebu a will to resist.” The next year, he also received a Silver Star and a Bronze Star. The Philippine government, too, awarded Jim, with the Distinguished Service Star. His brother Walt posthumously received the Distinguished Service Cross, as well as a Silver Star.

Walt Cushing was born to greatness. In his short life, he achieved an impressive string of accomplishments. When war came he transitioned from successful gold miner to legendary resistance leader almost overnight. The admiration and loyalty his guerrillas felt for their commander was boundless. His longtime friend, Captain M. B. Ordun, said Walt was “utterly fearless and bold to the point of foolhardiness. His sense of fair play and his daring exploits against the enemy won for him the almost godlike devotion of his followers.” In 1949, Walt’s remains were moved from their Philippines burial site to the Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery in San Diego, where family members still visit his grave.

Jim Cushing had greatness thrust upon him. Before the war, he was just another middling mining engineer with a fondness for drink. When war came, he, like his brother, transitioned into a guerrilla leader of extraordinary repute. Descriptions of the seventh brother’s deeds echo those of the fifth—that he was, according to his fellow guerrillas, “worshipped by his soldiers, and too brave for his own good.”

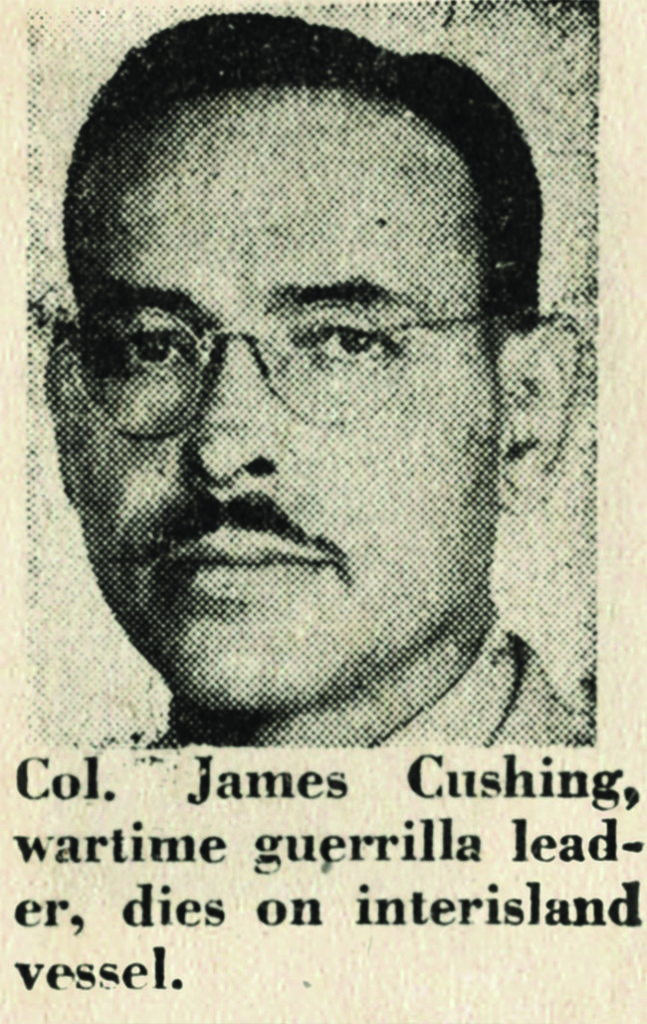

With the war won, Jim’s greatness quickly faded. In about 1950, he moved down to Palawan, in the southwest Philippines, in an attempt to restart his moribund mining career, but it didn’t work out. He ended up living in poverty and obscurity, dependent upon handouts from old friends.

On August 26, 1963, Jim suffered a fatal heart attack aboard an inter-island ferry. He was only 53. Though he was eligible for interment at the Manila American Cemetery, Jim had been adamant about being buried at nearby Libingan ng mga Bayani—the Philippines’ “Heroes Cemetery.” The Filipino people accorded him a full military funeral, his flag-covered coffin borne on a horse-drawn caisson, followed by a solemn procession of Filipino war veterans. As a three-volley rifle salute rang through the still air, Jim Cushing was laid to rest among the guerrilla patriots with whom he had fought side by side in the struggle to free their homeland. ✯