Narcissistic ne’re-do-well tries to conquer himself a country

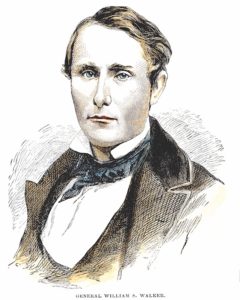

WILLIAM WALKER was a young man in a hurry but he couldn’t decide where he was going. In 1838, at 14, he graduated from the University of Nashville. At 19, he earned a medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania. But he didn’t enjoy doctoring, so he studied law in New Orleans. Lawyering also failed to thrill him, so he became a newspaper editor. Still restless, he sailed to California during the Gold Rush and became a newspaperman in San Francisco, where he concocted the scheme that would make him famous: Walker decided he would raise a private army, conquer a chunk of Latin America, and become a military dictator.

Traditionally, kings and generals monopolized the pleasures of conquest and dictatorship, but Walker believed they should be available to men like him–superior men of a superior race. A small white fellow—5’2”, 120 pounds—he had big schemes. In October 1853, he appointed himself a colonel, recruited 45 men, and sailed out of San Francisco to conquer northwestern Mexico.

Grabbing pieces of Mexico was not an original idea. In 1836, American settlers in a Mexican province revolted, declaring the place—Texas—an independent republic. In 1846, the United States provoked and won a war with Mexico, then forced the losers to sell what would become the states of California, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, and Utah, plus parts of Wyoming and Colorado. Many Americans believed they had a “manifest destiny” to rule the entire continent. Some, known as “filibusters,” attempted to conquer foreign countries for themselves.

Invading Mexico made Walker the most famous of the filibusters.

At first, the invasion went well. Walker and his men landed in the Mexican town of La Paz in Baja California and captured the territorial governor. Walker issued a proclamation declaring Baja “the Republic of Lower California” and himself its president. He seized the town of Ensenada, where reinforcements from San Francisco joined his original 45.

Mexican forces counterattacked, killing some filibusters and capturing Walker’s ship. Undaunted, Walker issued another proclamation, announcing that he was annexing Sonora, the province abutting Baja California.

That was a bold move, considering Walker had not set foot in Sonora. He soon invaded Sonora but failed to conquer the province.

Defeated, Walker and 34 filibusters fled to the American border in May 1854. “I am Colonel William Walker,” he announced. “I wish to surrender my force to the United States.”

That October, the United States charged Walker under the Neutrality Act, which forbids Americans from invading other countries, and tried him in San Francisco. But filibustering was popular there, and so was Walker. After eight minutes of deliberation, the jury acquited him.

Feeling vindicated, Walker decided to conquer Nicaragua, an unlikely nexus between America’s Atlantic and Pacific coasts.

Travelers sailed from New York to Nicaragua’s Caribbean side, then went by riverboat to the Pacific coast to board ships for San Francisco. Shuttling Americans was good business; one of America’s richest men, Cornelius Vanderbilt, owned the Accessory Transit Company, the riverboat concern.

Location made Nicaragua valuable. What made Nicaragua vulnerable was a civil war that its people had been fighting for decades.

Two main Nicaraguan factions were the Legitimists and the Liberals. Walker cut a deal with the Liberals: he’d fight on their side if they would give him land grants.

In May 1855, Walker sailed out of San Francisco with 57 men. In Nicaragua, he formed an army made up of Liberal soldiers and American filibusters and launched a surprise attack that captured Grenada, the Legitimist stronghold. He set up a new Nicaraguan government, naming himself commander of the army and appointing a local politician his puppet president.

But that didn’t satisfy Walker. In June 1856, he staged a bogus presidential election and declared himself victor. On inauguration day, he paraded through Grenada as a band played “Yankee Doodle.” Then he started issuing proclamations. One of these legalized slavery. Another seized land owned by “enemies of the state,” to be sold to his soldiers—which, Walker explained, would “place a large portion of the country in the hands of the white race.”

He also seized the Accessory Transit Company. Big mistake. Vanderbilt dispatched an agent to Costa Rica, Nicaragua’s southern neighbor, with $40,000 in gold.

The agent, aided by the gold, convinced the Costa Ricans to invade Nicaragua and overthrow Walker. Soon, northern neighbors Honduras and Guatemala dispatched troops to fight Walker. When his foes attacked, Walker ordered Grenada destroyed. Swigging looted liquor, his filibusters spent days burning Nicaragua’s most beautiful city.

In retreat, they left a sign that read “Aqui fue Grenada”—Here was Grenada.

A few months later, at a Nicaraguan port, Walker surrendered to the captain of a U.S. Navy ship and sailed home.

He lectured to cheering crowds in New Orleans, Memphis, and New York, blaming his defeat on the U.S. State Department and Northern abolitionists, and urging his countrymen to help him fight for “the Americanization of Central America.”

As Walker basked in his New York fans’ applause, a ship docked at Manhattan carrying 138 veterans of his defeated army.

Emaciated and sick, the former filibusters told reporters that Walker was a coward who’d deserted them in Nicaragua.

Walker left New York without answering his former compatriots’ charges and headed south to raise money for another invasion.

In November 1857, Walker and 270 filibusters sailed out of Mobile Bay. A U.S. Navy gunship followed. Walker landed near Greytown, Nicaragua; U.S. Marines arrested him.

“You and your men are a disgrace to the United States,” Hiram Pauling, the navy ship’s commander, told Walker.

President James Buchanan agreed. “That man has done more injury to the commercial & political interests of the United States than any man living,” Buchanan said.

In June 1858, the United States again charged William Walker with violating the Neutrality Act. The trial, in New Orleans, ended in a hung jury. Federal prosecutors opted not to re-try.

Feeling vindicated again, Walker once more toured the South, recruiting volunteers for yet another invasion. He wrote The War in Nicaragua, a book defending his dictatorship and his legalization of slavery: “With the Negro slave as his companion, the white man would become fixed to the soil; and together they would destroy the power of the mixed race, which is the bane of the country.”

Obstinate and obsessed, Walker decided to conquer Honduras. On August 5, 1860, he and 91 filibusters landed near Trujillo, on that country’s Caribbean coast, and captured a fort. But the British warship Icarus arrived—the royal colony now known as the nation of Belize was nearby–and demanded the filibusters’ surrender. Walker and company fled, skirmishing with Honduran soldiers before surrendering to the British.

“I am William Walker, president of Nicaragua,” he told his captors.

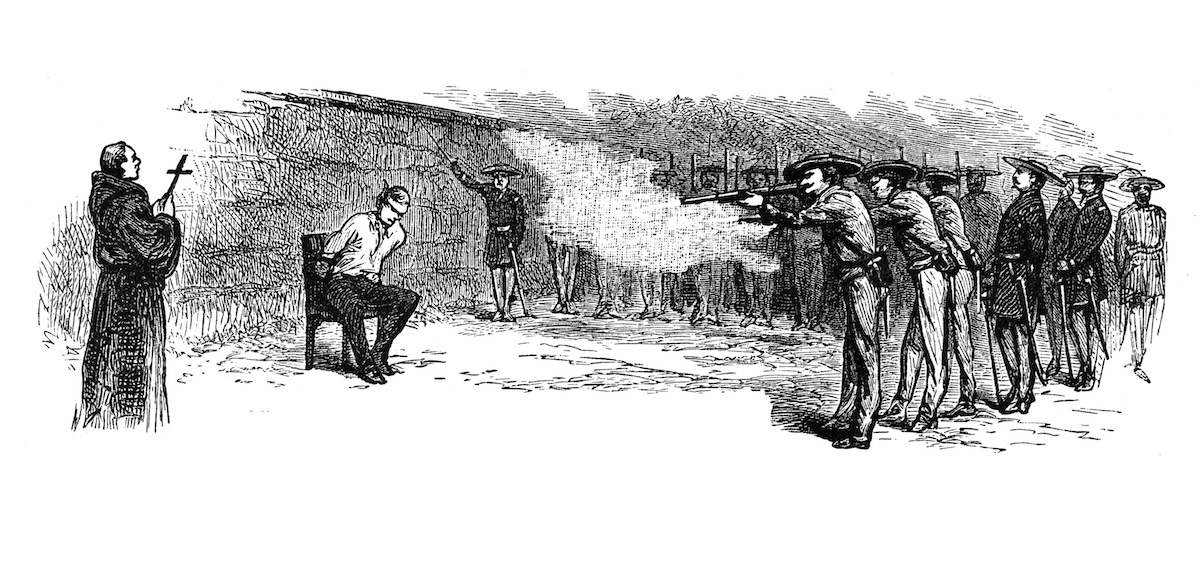

Walker expected the British to send him home. Instead, they handed him over to the Hondurans. On September 12, 1860, barefoot Honduran soldiers marched Walker through a jeering crowd and sat the most famous filibuster against a wall, where a firing squad waited.

Refusing a request to ship his corpse home, the Hondurans buried William Walker in Trujillo and sent his sword south, a gift to the Nicaraguan government. ✯